The process of adjusting the barrels so that the bullet leaves each barrel at the same point in space is known as “regulation” and a rifle that has been successfully adjusted in this way is said to be “regulated”.

Regulation must be distinguished from sighting-in. Regulation is the process leading to both barrels shooting to the same point of impact, while sighting-in involves adjusting the sights so that the point of aim co-incides with that point of impact – see Building Double Rifles on Shotgun Actions, W. Ellis Brown at p. 150.

The process will be effective only for a bullet travelling at the same speed as the bullet with which the rifle was regulated. This information was so important that barrels of blackpowder rifles were often stamped with the load for which it was regulated e.g. “regulated for xx grain bullet and xxx drams of blackpowder“. With modern rifles, the manufacturer will specify the ammunition with which it was regulated. Buyers of custom rifles can choose the ammunition to be used in the regulation process.

This, of course, depends on manufacturers keeping to a consistent standard. For example, the 470NE cartridge was designed to produce a muzzle velocity of 2150fps with a 500-grain bullet. Modern ammunition is designed to provide this same performance. There is no point pushing the bullet faster (leaving aside the increased pressure) since the result would be that double rifles using it would cross-fire. Of course, this is of little help if you have a rifle for which ammunition is no longer commercially made.

Westley Richards describes the regulation process as follows:

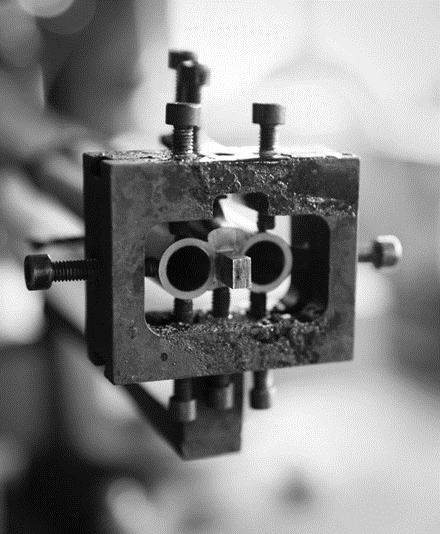

“Having shot the rifle with 4 shots to confirm accuracy the rifle is then disassembled, front sight removed and the barrels are placed in a regulating jig as seen above. This jig supports the barrels and allows individual adjustments through the use of 9 hex head bolts. There is a wedge in the muzzle of the rifle which aides in the barrels being drawn either inwards (draw wedge out) and apart (push wedge in).

Having set the barrels firmly in the jig, the muzzle ends are heated up to a point where the solder holding the barrels together begins to melt, at this point the barrels can be independently moved in any direction to obtain the correct convergence and point of aim. This is done by relieving the opposing bolt and tightening the other side. Adjustments are made in small movements of about .0010″ a time although this is where the process becomes one of feel and knowledge rather than pure measurement. The barrels are then allowed to cool down completely after which they are cleaned and the process begins again and is repeated until the desired result is achieved.”

And they provide a picture of the jig they use:

Note that the jig allows the regulator to change the angle of the barrels relative to each other and the breach face both vertically and horizontally.

The adjustment process is not deterministic. In other words, you cannot simply enter a series of measurements or other values into a formula and produce a precise measurement for the barrels. The process is not one of trial-and-error, since the riflemaker knows what adjustment is needed to produce the desired result, but it does depend on the handling characteristics of each rifle.

Therefore, the rifle must be shot from the shoulder in the regulation process, rather than from a machine rest. This is because the regulation process is linked to the movement of the barrels as the rifle is fired. A rifle fired from a fixed rest will not move in the same way as if it is fired from the shoulder and so is free to move with the recoil.

You also cannot use a laser bore-sighting tool to regulate a double rifle. The laser cannot provide a measurement precise enough to adjust the barrels. You would need a very fine laser dot at a considerable distance to be able to measure a deflection of thousandths of an inch. Old-fashioned mechanical means are more practical.

Perhaps the best description of the process in modern literature is to be found in Building Double Rifles on Shotgun Actions by W. Ellis Brown. His book is a fascinating description of how to build a double rifle by adding a pair of rifled barrels to a shotgun action. The process is beyond my limited mechanical skills, but the book contains numerous practical observations on double rifles.

He describes the regulation process in this way:

“Regulation, then, can be defined as the process used to determine the mechanical compensation (convergence) for the length of time a projectile of a given weight is in the barrel of a double rifle. Being ‘regulated’ is the result of the process” (at p. 150)

His process for regulation involves using a spacer and shims between the barrels so that they converge. He then shoots the rifle and adds or removes shims to change the convergence angle, until both barrels shoot to a similar point of aim (more on this below). Rather than soldering the barrels together through this process (like Westley Richards) he uses a hose clamp to hold the barrels together. This is much quicker to adjust and avoids the need to melt the solder holding the barrels together before making each adjustment.

Much of his book focuses on the convergence of the barrels in the horizontal plane, but he also mentions in passing, that:

“you will have to move the barrels up and down in relation to the horizontal centerline of the gun as you tighten the band clamp to get them to hit on the same elevation plane” (at p. 157)

Ideally the shots should strike the target the same distance apart as the barrels (rather than in the same place). So if the centres of the barrels are 1 inch apart, the shots should fall on the target 1 inch apart. In this way the shots are travelling parallel with each other and the line of sight. The sights will need to be adjusted for different distances, but as discussed above, sighting-in and regulation serve different purposes. In other words, the shots would neither converge nor diverge in a perfectly regulated double rifle. Since nothing is perfect, every rifle will have some tendency to one or the other.

But there is a modern mechanical means to regulate rifles. The Blaser S2 has each barrel free-floated inside a tube supported by O-rings. Screws set in the tube at the muzzle allow the user to apply pressure to a barrel and so move it within the tube. In effect, a much smaller version of the jig described above is set into the tube. It seems similar in concept to the screws used in adjusting an einstucklauf (an insert that adapts a barrel to use a smaller cartridge). Another method involves a barrel clamp at the muzzle that allows the user to move the left barrel relative to the right barrel to achieve the adjustment needed and then to lock the barrels in place.

I found this description of one user’s experience of regulating a Blaser S2:

“First get a flat piece of board (wood/ceramic). Cut a hole in the board so that the monoblock hooks can fit in and the end of the monoblock is near the end. Lay it down flat and then use a wood clamp to clamp the monoblock tight to the board tight. The muzzle should just be over the other end of the board so that you can access the torx screw on the barrel cap whilst it is pinned down. Next insert two, 1.5mm spaces under each barrel. Slightly loosen the torx screw. The split will open and allow the barrels twist. Now clamp each barrel really tight to board with the spaces underneath. When everything is tight then retightened the torx screw on the barrel cap and the split will close and tighten on the left barrel. This will lock the left barrel relative to the right barrel.

Test fire and you should see that both bullets are level or very close to level. If not repeat with different spaces if required until they are level. I’d then consider putting Loctite on the screw so it never easily comes loose again.

Now if the barrels are crossing too early, you need to loosen the wedge in the centre. There are three 2mm allen key screws there. Loosen the two outer ones first then with only 1/8 of a turn slowly undo until you get the barrels crossing at the regulated distance.”

Merkel have a similar system. However, the owners’ manual warns:

“Over-and-under combination double rifles and ‘Bergstutzen’ rifles are equipped with a free-floating bottom rifled barrel that allows adjustment in elevation and windage. Any regulation of the points of impact of lower and upper barrel must only be performed by persons authorized by Merkel” (Merkel B3 & B4 Owner’s Manual at p. 17)

The benefit of these systems is that the factory can regulate the rifle more quickly (and thus at lower cost) than the system used by makers such as Westley Richards. It also allows the rifle to be re-regulated in the future to use the ammunition available to the user at that time, or to use a bullet of a different weight.

But what if you cannot get the ammunition that was used to regulate the rifle, or your rifle does not have an adjustable regulation system? I will consider that in Part 4 …